The world-renowned Sequoyah National Research Center in Little Rock

Tucked away in the Fine Arts Building on the grounds of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock is a world renowned destination to learn about Native American history and heritage: the Sequoyah National Research Center. These archives preserve all forms of expression by Native Americans.

“We are the only research center dedicated to the research of Native Americans in the state," said Erin Fehr, assistant director and archivist at the Sequoyah National Research Center, SNRC. “This is a very unique gem for Arkansas. We have people come from all over the world to research here.”

Most of this expression is in print form but there are also works archived for film, music, art, oral histories and more.

“We don’t know anybody who has tried what we have done,” said Dr. Daniel Littlefield, director of the Sequoyah National Research Center.

The center has taken both an international and contemporary approach in helping keep alive the history of Native Americans. When they first began the center, it was difficult to find anybody who was keeping a record of contemporary Native American life. “It brought up the question , 'who is going to tell the story 50 to 100 years from now,” said Littlefield. “Is it going to be the same non-Indians that told it in the past or will the voice of what they have to say about their own society play a role in it?”

The center was first known as the American Native Press Archives when it was created in the early 1980s by Littlefield and James Parins, who both worked in the English Department at UALR at the time. It is now considered the major repository of contemporary Native materials in the world.

“Our newspapers are mostly what we are known for even though we have large manuscript collections but we have over 2,500 individual titles in our newspaper collection,” said Fehr. “And we cover over 200 tribes within the collection that spans both the U.S. and Canada. As far as manuscript collections we have about 100 that are processed.”

To put the collection further in context, the center was part of a project a few years ago where a portion of their collection, over 100,000 pages, was digitized. This amounted to less than 1% of their collection. SNRC also has around 200 pieces of art, which are being stored by the university’s art department. It also houses the personal library of Robert Conley, a prolific and award-winning Cherokee author who wrote around 80 books in his lifetime.

SNRC is open to visitors for research but one of the most misunderstood aspects is that they are a genealogy research center. “People think we do genealogy and we don’t,'' said Fehr. “We do point people in the right direction. But they think this is where they can come to do genealogy. And we send them to the Arkansas State Archives.”

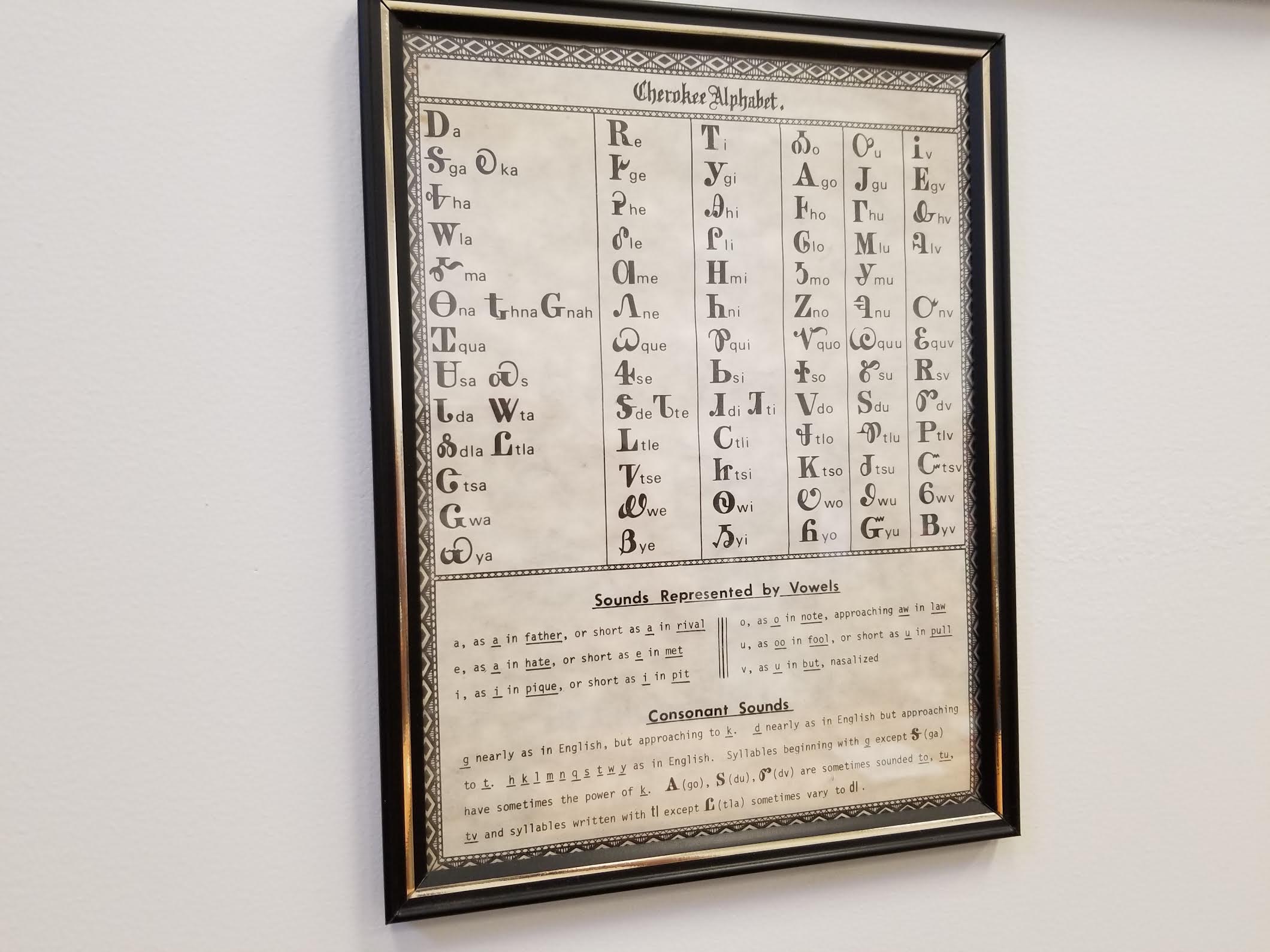

The name of the center pays homage to Sequoyah, a Cherokee who has a place in history as the creator of the alphabet for the Cherokee language. What some might not realize is that Sequoyah was in Arkansas when he perfected his system of writing.

“That’s why we named it Sequoyah National Research Center, '' said Littlefield. “Because we were interested in Native writers and he was a linguist … he came west primarily to teach the western Cherokees the system of writing so they could write back to the east. He wrote back to his daughter and she would translate his letters to people there. The government officials finally saw what he was doing and adopted that system of writing as the official writing of the Cherokee language.” Up until that point the Cherokee language was all oral.

Another interesting Arkansas connection is that of Elijah Horner of Mena. He served in both World War I and World War II and led the Choctaw code talkers in World War I. “Most people are aware that the Navajos served as code talkers in World War II but there were also 33 other tribes that served in World War II,” said Fehr. “The Choctaws in World War I are considered to be the first. They used their Native language in the war. There were four other tribes that also served as code talkers in the first world war. They used their native languages to transmit messages that could not be translated by the Germans that were listening in. Most people aren't aware that there were 12,000 American Indians and Alaskan natives that served in that first world war and most of them were not even citizens at that time.”

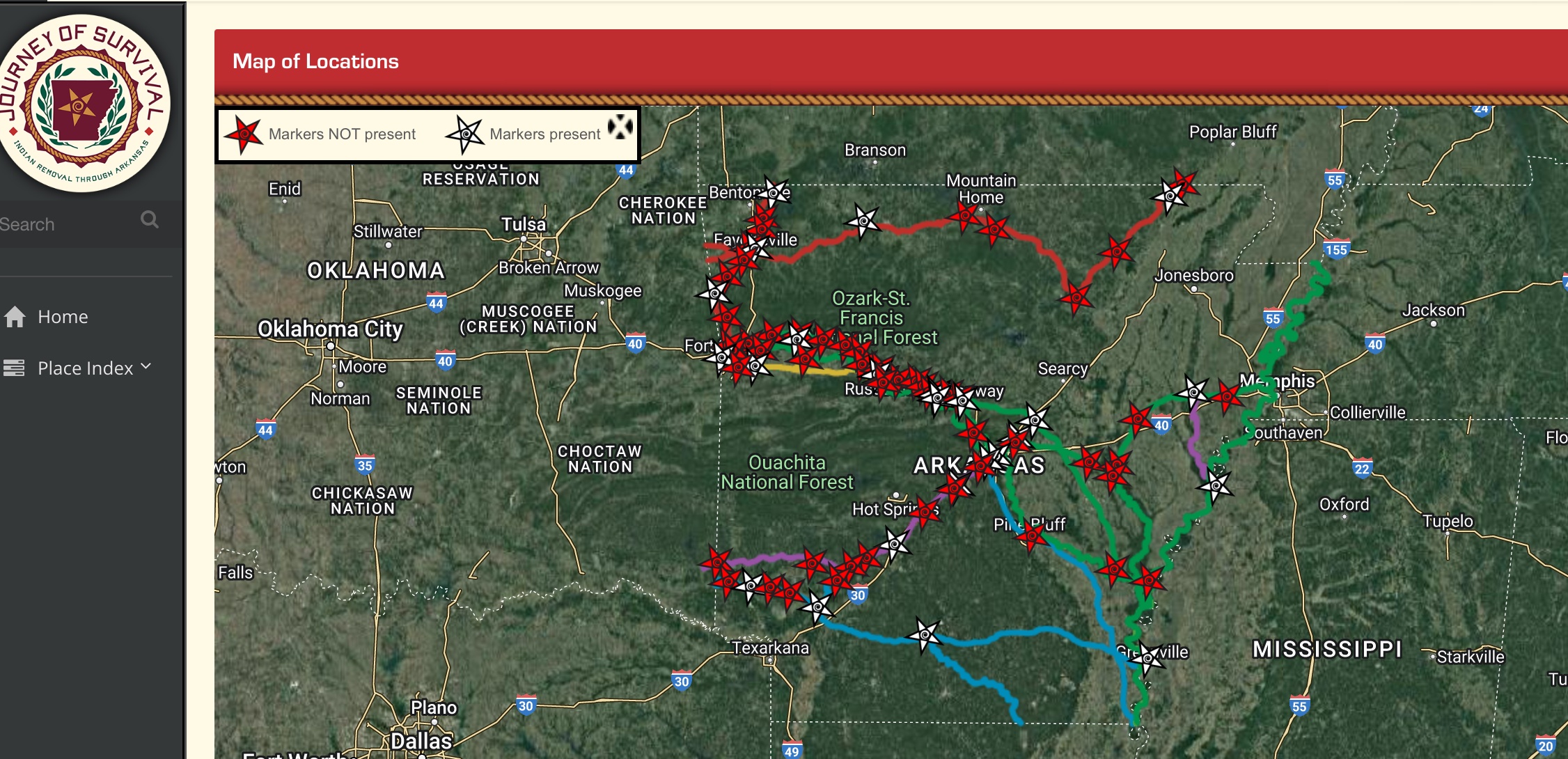

Speaking of Arkansas history, the center has just completed a landmark project called "Journey of Survival: Indian Removal Through Arkansas.” There is a large touchscreen kiosk onsite to view a wealth of information related to the history of Indian removal through the state. There is also a website you can view that is part of the project, Journeyofsurvival.org, where you can learn about more than 80 sites in Arkansas that are tied to this history. The project is “the most significant study of Indian history in Arkansas that has been done,” said Littlefield.

For those interested in visiting some of the historic sites that are part of this project, the website includes detailed information about each spot featured, including whether historical markers are present to see or other features.

Along with the Sequoyah National Research Center, Native American history can be found across the state. There are various places to learn more including the Trail of Tears Park on the UALR campus. This park pays homage to the Choctaw and Chickasaw removal as well as the Southwest Trail, a path once traveled by the Indians. On the second floor of the Fine Arts Building at UALR you can see a small sample of the collection of Dr. J. W. Wiggins, who donated his collection of contemporary Native American art to the university.

The Historic Arkansas Museum in Little Rock has a permanent exhibit that highlights the tribes in the state. “They look at both the history of the tribes of the state and they have contemporary voices that talk about their time in the state of Arkansas,” said Fehr.

Fehr added that Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville has done a good job of including contemporary Native art within their museum. Also in Bentonville is the Museum of Native American History.

Plum Bayou Mounds Archeological State Park, formerly Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park, in Scott gives a prime overview of Indian prehistory.

At Village Creek State Park in Wynne you can walk on a section of the Trail of Tears. “If people are interested in Trail of Tears Indian removal, this is a place I would tell them to visit,” said Littlefield.

The trail at Village Creek State Park is part of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, which is a project of the National Park Service and traverses portions of nine states, including Arkansas. Other state parks are also part of this national historic trail and one can read more about this via this detailed and informative article, which was written by a state park interpreter.

Pea Ridge National Military Park in Garfield was the place where many Cherokees entered the state.

A lot of Indian territory history was written in Fort Smith and this history is preserved at spots like the Fort Smith National Historic Site.

And more sites around the state that highlight Native American history can be found via this article.